1

- 14

of 14 LOTS

1

‘Trofeo’ workshop, Venice; second quarter, 18th century. Silversmith: probably Andrea Fulici, assayer: Zuanne Cottini

‘Trofeo’ workshop, Venice; second quarter, 18th century. Silversmith: probably Andrea Fulici, [..]

1

Free Bid

‘Trofeo’ workshop, Venice; second quarter, 18th century. Silversmith: probably Andrea Fulici, assayer: [..]

‘Trofeo’ workshop, Venice; second quarter, 18th century. Silversmith: probably Andrea Fulici, [..]

Estimate

€ 30.000 / 40.000

2

AN ASSORTMENT OF PLATES FROM THE ‘VEDUTE DEL REGNO’ (VIEWS OF THE KINGDOM) PRESENTATION SERVICE, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE ‘SERVIZIO DELL’OCA’. NAPLES, REAL FABBRICA FERDINANDEA, 1793-1795

AN ASSORTMENT OF PLATES FROM THE ‘VEDUTE DEL REGNO’ (VIEWS OF THE KINGDOM) PRESENTATION SERVICE, [..]

2

Free Bid

AN ASSORTMENT OF PLATES FROM THE ‘VEDUTE DEL REGNO’ (VIEWS OF THE KINGDOM) PRESENTATION SERVICE, OTHERWISE [..]

AN ASSORTMENT OF PLATES FROM THE ‘VEDUTE DEL REGNO’ (VIEWS OF THE KINGDOM) PRESENTATION SERVICE, [..]

Estimate

€ 10.000 / 15.000

Sold

3

A DISH URBINO, WORKSHOP OF GUIDO DURANTINO, SIGNED WITH THE MONOGRAM AM, F.S., FORMERLY THE WORKSHOP OF FRANCESCO DE SILVANO (?), 1542

A DISH URBINO, WORKSHOP OF GUIDO DURANTINO, SIGNED WITH THE MONOGRAM AM, F.S. , FORMERLY THE WORKSHOP [..]

3

Free Bid

A DISH URBINO, WORKSHOP OF GUIDO DURANTINO, SIGNED WITH THE MONOGRAM AM, F.S., FORMERLY THE WORKSHOP [..]

A DISH URBINO, WORKSHOP OF GUIDO DURANTINO, SIGNED WITH THE MONOGRAM AM, F.S. , FORMERLY THE WORKSHOP [..]

Estimate

€ 40.000 / 60.000

Sold

4

Gerrit van Honthorst, also known as Gherardo delle Notti

Gerrit van Honthorst, also known as Gherardo delle Notti (Utrecht 1590 – 1656) A BOY BLOWING ON [..]

4

Free Bid

Gerrit van Honthorst, also known as Gherardo delle Notti

Gerrit van Honthorst, also known as Gherardo delle Notti (Utrecht 1590 – 1656) A BOY BLOWING ON [..]

Estimate

€ 300.000 / 500.000

Sold

5

Gaspar van Wittel (Gaspare Vanvitelli)

Gaspar van Wittel (Gaspare Vanvitelli) (Amersfoort (Utrecht) 1652/53 – Rome 1736) A VIEW OF THE [..]

5

Free Bid

Gaspar van Wittel (Gaspare Vanvitelli)

Gaspar van Wittel (Gaspare Vanvitelli) (Amersfoort (Utrecht) 1652/53 – Rome 1736) A VIEW OF THE [..]

Estimate

€ 500.000 / 800.000

6

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta (Venice 1682-1754) VIRGIN AND CHILD oil on canvas, cm 77x61

An export [..]

6

Free Bid

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta (Venice 1682-1754) VIRGIN AND CHILD oil on canvas, cm 77x61

An export [..]

Estimate

€ 80.000 / 120.000

7

Florentine manufacture, early 17th century

Florentine manufacture, early 17th century A TABLETOP in polychrome stone commesso work, cm. 101 [..]

7

Free Bid

Florentine manufacture, early 17th century

Florentine manufacture, early 17th century A TABLETOP in polychrome stone commesso work, cm. 101 [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 90.000

Sold

8

A PAIR OF MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COMMODES, PAPAL STATE - ROME

A PAIR OF MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COMMODES, PAPAL STATE - ROME poplar carcase, with elm and walnut burl [..]

8

Free Bid

A PAIR OF MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COMMODES, PAPAL STATE - ROME

A PAIR OF MID-EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COMMODES, PAPAL STATE - ROME poplar carcase, with elm and walnut burl [..]

Estimate

€ 40.000 / 60.000

Sold

9

A PAIR OF MONUMENTAL TORCHÈRES, LONDON, 1830 CA.

A PAIR OF MONUMENTAL TORCHÈRES , LONDON, 1830 CA.

in gilded bronze. With a shaped triangular [..]

9

Free Bid

A PAIR OF MONUMENTAL TORCHÈRES, LONDON, 1830 CA.

A PAIR OF MONUMENTAL TORCHÈRES , LONDON, 1830 CA.

in gilded bronze. With a shaped triangular [..]

Estimate

€ 30.000 / 50.000

Sold

10

Osvaldo Borsani

Osvaldo Borsani

(Varedo 1911 – Milan 1985)

Lucio Fontana

(Rosario de Santa Fè 1899 [..]

10

Free Bid

Osvaldo Borsani

Osvaldo Borsani

(Varedo 1911 – Milan 1985)

Lucio Fontana

(Rosario de Santa Fè 1899 [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 90.000

Sold

11

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan. 1891-1972)

A PAIR OF CORNER CABINETS FOR THE CONTINI BONACOSSI RESIDENCE, VILLA [..]

11

Free Bid

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan. 1891-1972)

A PAIR OF CORNER CABINETS FOR THE CONTINI BONACOSSI RESIDENCE, VILLA [..]

Estimate

€ 90.000 / 120.000

Sold

12

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan. 1891-1972)

A COFFEE TABLE FOR THE CONTINI BONACOSSI RESIDENCE, VILLA VITTORIA, FLORENCE, [..]

12

Free Bid

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan. 1891-1972)

A COFFEE TABLE FOR THE CONTINI BONACOSSI RESIDENCE, VILLA VITTORIA, FLORENCE, [..]

Estimate

€ 40.000 / 60.000

Sold

13

Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin

Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin

(Toulouse 1860 - La Bastide-du-Vert 1943)

A CHACUN SA CHIMÈRE [..]

13

Free Bid

Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin

Henri-Jean-Guillaume Martin

(Toulouse 1860 - La Bastide-du-Vert 1943)

A CHACUN SA CHIMÈRE [..]

Estimate

€ 100.000 / 150.000

14

Free Bid

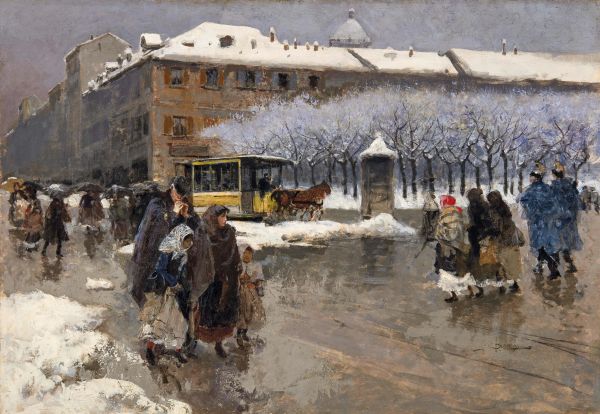

Mosè Bianchi

Mosè Bianchi

(Monza 1840 - 1904)

OLD MILAN

oil on cardboard, cm 53,5x77

signed [..]

Estimate

€ 50.000 / 70.000

Sold

1

- 14

of 14 LOTS

![AN ASSORTMENT OF PLATES FROM THE ‘VEDUTE DEL REGNO’ (VIEWS OF THE KINGDOM) PRESENTATION SERVICE, OTHERWISE [..]](https://images.pandolfini.it/@img/_large/393acf49fbf34f948241399a7521f8943f78f600.webp/-an-assortment-of-plates-from-the-8216vedute-del-.webp)

![A DISH URBINO, WORKSHOP OF GUIDO DURANTINO, SIGNED WITH THE MONOGRAM AM, F.S., FORMERLY THE WORKSHOP [..]](https://images.pandolfini.it/@img/_large/926e829db6a51347090ac325e12e15cf9afae030.webp/-a-dish-urbino-workshop-of-guido-durantino-signed-.webp)