1

- 27

of 27 LOTS

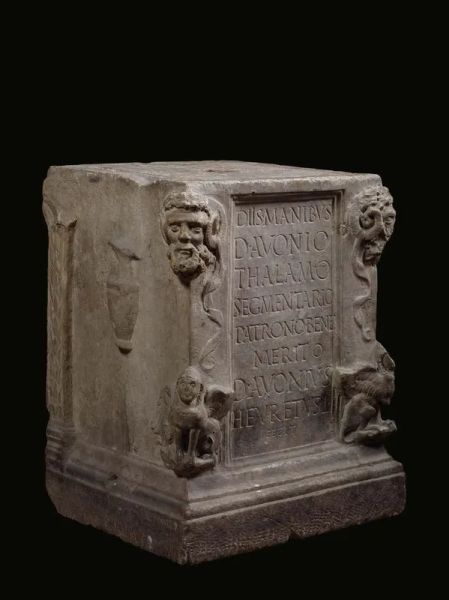

1

ALTAR

ALTAR ROMAN, 2 ND TO 3 RD CENTURY AD

Fine grain white marble, sculpted, polished, and finished off [..]

1

ALTAR

ALTAR ROMAN, 2 ND TO 3 RD CENTURY AD

Fine grain white marble, sculpted, polished, and finished off [..]

Estimate

€ 20.000 / 30.000

Sold

2

STATUE OF ARTEMIS

STATUE OF ARTEMIS

NEO-ATTIC CRAFTSMANSHIP, END OF THE 1 ST CENTURY B.C.

Medium grain white marble, sculpted [..]

2

STATUE OF ARTEMIS

STATUE OF ARTEMIS

NEO-ATTIC CRAFTSMANSHIP, END OF THE 1 ST CENTURY B.C.

Medium grain white marble, sculpted [..]

Estimate

€ 80.000 / 120.000

Sold

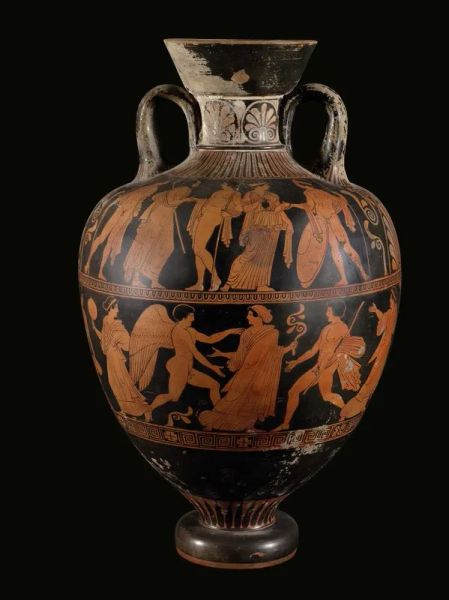

3

Amykos Painter

Amykos Painter

(active 430-410 BC)

LARGE RED-FIGURE PSEUDO-PANATHENAIC AMPHORA, LUCANIAN

Orange clay, [..]

3

Amykos Painter

Amykos Painter

(active 430-410 BC)

LARGE RED-FIGURE PSEUDO-PANATHENAIC AMPHORA, LUCANIAN

Orange clay, [..]

Estimate

€ 30.000 / 50.000

Sold

4

David Willaume I

David Willaume I (Metz 1658-London 1744)

EWER, LONDON, 1700 [..]

Estimate

€ 10.000 / 15.000

Sold

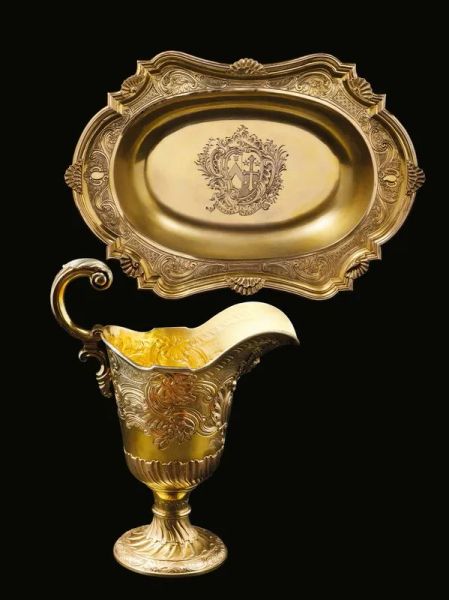

5

Ayme Videau

Ayme Videau

(active from 1723 to 1775)

EWER WITH BASIN, LONDON, 1755

in vermeil engraved and [..]

5

Ayme Videau

Ayme Videau

(active from 1723 to 1775)

EWER WITH BASIN, LONDON, 1755

in vermeil engraved and [..]

Estimate

€ 28.000 / 35.000

6

Paul Storr

Paul Storr

(Westminster 1771 - Tooting 1844)

CENTERPIECE, LONDON, 1805

silver, 27 [..]

Estimate

€ 12.000 / 18.000

7

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan 1891-1972)

COFFEE TABLE, 1937

Chestnut briar root and crystal

Made by Giordano [..]

7

Gio Ponti

Gio Ponti

(Milan 1891-1972)

COFFEE TABLE, 1937

Chestnut briar root and crystal

Made by Giordano [..]

Estimate

€ 30.000 / 45.000

Sold

8

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIAZZETTA

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIAZZETTA

(Venezia 1683 – 1753)

Coppia di musicanti

Gessetto nero [..]

8

Free Bid

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIAZZETTA

GIOVANNI BATTISTA PIAZZETTA

(Venezia 1683 – 1753)

Coppia di musicanti

Gessetto nero [..]

Estimate

€ 25.000 / 35.000

Sold

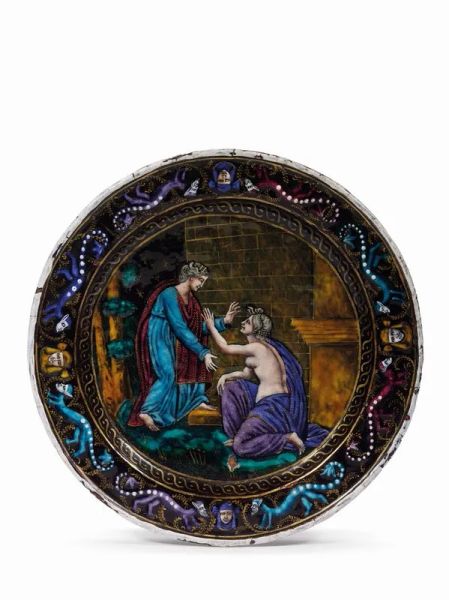

9

Limoges, mid-16th century

Limoges, mid-16 th century

JUNO REJECTING PSYCHE

Copper plate with enamel and gold, 21 cm diameter [..]

9

Limoges, mid-16th century

Limoges, mid-16 th century

JUNO REJECTING PSYCHE

Copper plate with enamel and gold, 21 cm diameter [..]

Estimate

€ 12.000 / 18.000

10

Ginori Manufactory, Doccia

Ginori Manufactory, Doccia

SNUFFBOX KNOWN AS “OF THE HERESIARCHS”, CA. 1760-1765

Polychrome [..]

10

Ginori Manufactory, Doccia

Ginori Manufactory, Doccia

SNUFFBOX KNOWN AS “OF THE HERESIARCHS”, CA. 1760-1765

Polychrome [..]

Estimate

€ 20.000 / 30.000

Sold

11

Imperial Lapidary Works

Imperial Lapidary Works

PAIR OF ORNAMENTAL VASES, RUSSIA, FIRST QUARTER OF THE 19TH CENTURY

Malachite [..]

11

Imperial Lapidary Works

Imperial Lapidary Works

PAIR OF ORNAMENTAL VASES, RUSSIA, FIRST QUARTER OF THE 19TH CENTURY

Malachite [..]

Estimate

€ 20.000 / 30.000

Sold

12

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17TH CENTURY

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17 TH CENTURY

Carved wood, veneered ebony and tortoiseshell [..]

12

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17TH CENTURY

CABINET, NAPLES, SECOND HALF OF THE 17 TH CENTURY

Carved wood, veneered ebony and tortoiseshell [..]

Estimate

€ 80.000 / 120.000

13

A LOUIS XVI PAIR OF GIRANDOLES, FRANCE, CIRCA 1775

A LOUIS XVI PAIR OF GIRANDOLES, FRANCE, CIRCA 1775

Green granite and gilded and chiselled bronze; vases [..]

13

A LOUIS XVI PAIR OF GIRANDOLES, FRANCE, CIRCA 1775

A LOUIS XVI PAIR OF GIRANDOLES, FRANCE, CIRCA 1775

Green granite and gilded and chiselled bronze; vases [..]

Estimate

€ 80.000 / 120.000

14

RARE CENTRE DESK, LOMBARDY, THIRD QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURY

RARE CENTRE DESK, LOMBARDY, THIRD QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURY Veneered chestnut and chestnut briar, rounded [..]

14

RARE CENTRE DESK, LOMBARDY, THIRD QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURY

RARE CENTRE DESK, LOMBARDY, THIRD QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURY Veneered chestnut and chestnut briar, rounded [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 90.000

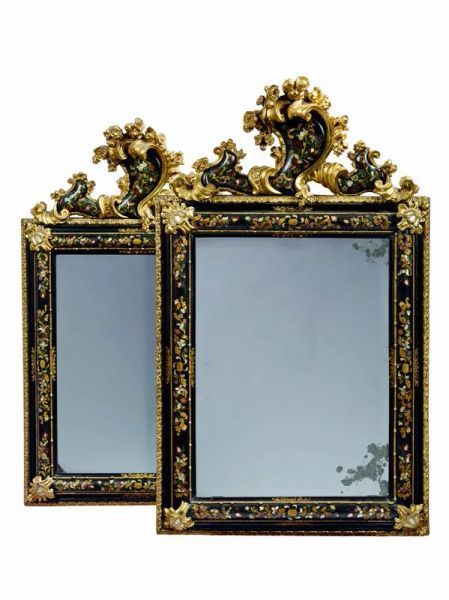

15

PAIR OF MIRRORS, VENICE, SECOND QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURYPAIR OF MIRRORS, VENICE, SECOND QUARTER OF [..]

PAIR OF MIRRORS, VENICE, SECOND QUARTER OF THE 18TH CENTURY

in ebonized, lacquered and gilded wood [..]

Estimate

€ 70.000 / 100.000

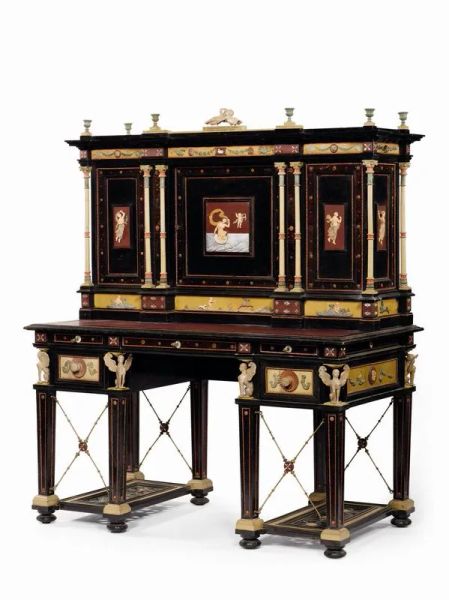

16

Regia Scuola di incisione sul corallo

Regia Scuola di incisione sul corallo

EBONY, LAVASTONE, GILT BRONZE, MOTHER-OF-PEARL, TORTOISESHELL [..]

16

Regia Scuola di incisione sul corallo

Regia Scuola di incisione sul corallo

EBONY, LAVASTONE, GILT BRONZE, MOTHER-OF-PEARL, TORTOISESHELL [..]

Estimate

€ 40.000 / 60.000

Sold

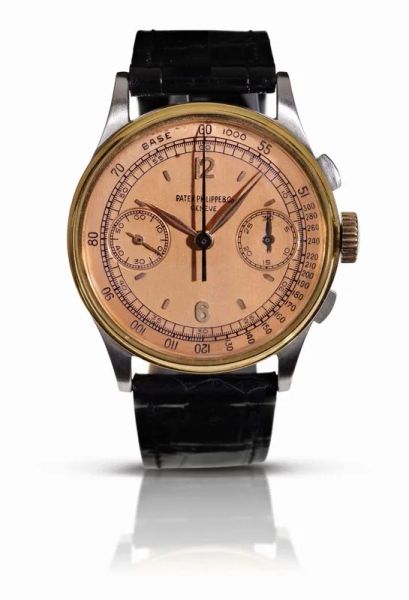

17

AN EXTREMELY FINE AND RARE STAINLESS STEEL AND 18K PINK GOLD CHRONOGRAPH WRISTWATCH, PATEK PHILIPPE , REF. 130, MOVEMENT NO. 867’038, CASE NO. 630’157, MANUFACTURED IN 1946, WITH PATEK PHILIPPE EXTRACT FROM THE ARCHIVE

RARO OROLOGIO DA POLSO CON CRONOGRAFO PATEK PHILIPPE, REF. 130, MOV. N. 867’038, CASSA N. 630’157, [..]

17

AN EXTREMELY FINE AND RARE STAINLESS STEEL AND 18K PINK GOLD CHRONOGRAPH WRISTWATCH, PATEK PHILIPPE [..]

RARO OROLOGIO DA POLSO CON CRONOGRAFO PATEK PHILIPPE, REF. 130, MOV. N. 867’038, CASSA N. 630’157, [..]

Estimate

€ 130.000 / 180.000

18

Domenico Pellegrini

Domenico Pellegrini

(Galliera Veneta 1759 - Rome 1840)

PORTRAIT OF FILIPPO AND COSTANZA DE MARINIS [..]

18

Domenico Pellegrini

Domenico Pellegrini

(Galliera Veneta 1759 - Rome 1840)

PORTRAIT OF FILIPPO AND COSTANZA DE MARINIS [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 80.000

19

Antonio Fontanesi

Antonio Fontanesi

(Reggio nell'Emilia 1818 - Turin 1882)

IL GUADO

oil on panel, 78,5x115 cm [..]

19

Antonio Fontanesi

Antonio Fontanesi

(Reggio nell'Emilia 1818 - Turin 1882)

IL GUADO

oil on panel, 78,5x115 cm [..]

Estimate

€ 130.000 / 160.000

Sold

20

Eugene Boudin

Eugène Boudin

(Honfleur 1824 - Deauville 1898)

TROUVILLE, LE RIVAGE

oil on canvas, 55,5x92,5 [..]

20

Free Bid

Eugene Boudin

Eugène Boudin

(Honfleur 1824 - Deauville 1898)

TROUVILLE, LE RIVAGE

oil on canvas, 55,5x92,5 [..]

Estimate

€ 100.000 / 150.000

Sold

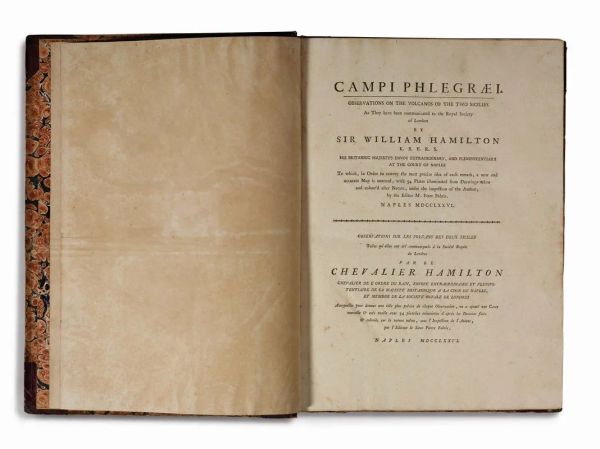

21

Sir William Hamilton

Sir William Hamilton

(Henley-on-Thames 1730 - London 1803)

CAMPI PHLEGRAEI. OBSERVATIONS ON THE [..]

21

Sir William Hamilton

Sir William Hamilton

(Henley-on-Thames 1730 - London 1803)

CAMPI PHLEGRAEI. OBSERVATIONS ON THE [..]

Estimate

€ 50.000 / 70.000

Sold

22

GRANDE VENTAGLIO DECORATO DA DUE ACQUARELLI DI GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 – 1887) E IMPREZIOSITO DA OLTRE 60 IMPORTANTI AUTOGRAFI E DEDICHE, DI CUI 14 AD OPERA DI CELEBRI MAESTRI DI MUSICA, LETTERATI E ATTORI, 1883 – 1993

LARGE FAN DECORATED WITH TWO WATERCOLORS BY GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 - 1887) AND ENHANCED BY OVER 60 IMPORTANT [..]

22

GRANDE VENTAGLIO DECORATO DA DUE ACQUARELLI DI GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 – 1887) E IMPREZIOSITO DA OLTRE [..]

LARGE FAN DECORATED WITH TWO WATERCOLORS BY GIACOMO FAVRETTO (1849 - 1887) AND ENHANCED BY OVER 60 IMPORTANT [..]

Estimate

€ 20.000 / 30.000

23

DEMI-PARURE, VAN CLEEF AND ARPELS, FINE ANNI '60, IN ORO GIALLO, TURCHESI E DIAMANTI

DEMI-PARURE, VAN CLEEF AND ARPELS, FINE ANNI '60, IN ORO GIALLO, TURCHESI E DIAMANTI

Composta di [..]

23

DEMI-PARURE, VAN CLEEF AND ARPELS, FINE ANNI '60, IN ORO GIALLO, TURCHESI E DIAMANTI

DEMI-PARURE, VAN CLEEF AND ARPELS, FINE ANNI '60, IN ORO GIALLO, TURCHESI E DIAMANTI

Composta di [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 80.000

Sold

24

Andrea Scacciati

Andrea Scacciati

(Firenze 1642-1710)

VASO DI FIORI ALL'APERTO, SU UNA PIETRA; SULLO SFONDO, [..]

24

Andrea Scacciati

Andrea Scacciati

(Firenze 1642-1710)

VASO DI FIORI ALL'APERTO, SU UNA PIETRA; SULLO SFONDO, [..]

Estimate

€ 40.000 / 60.000

25

Maestro della lunetta di via Romana,

Maestro della lunetta di via Romana,

alias Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli

(Firenze 1450-1526) [..]

25

Free Bid

Maestro della lunetta di via Romana,

Maestro della lunetta di via Romana,

alias Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli

(Firenze 1450-1526) [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 80.000

Sold

26

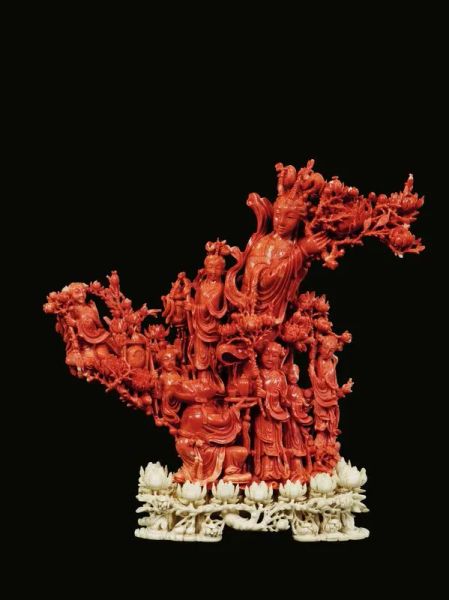

CARVING, CHINA, LATE QING DYNASTY, XIX CENTURY

CARVING, CHINA, LATE QING DYNASTY, XIX CENTURY Red coral, 24,5 cm high, 1965 g. weight Standing on a [..]

26

CARVING, CHINA, LATE QING DYNASTY, XIX CENTURY

CARVING, CHINA, LATE QING DYNASTY, XIX CENTURY Red coral, 24,5 cm high, 1965 g. weight Standing on a [..]

Estimate

€ 15.000 / 20.000

Sold

27

A GILT-LACQUERED BRONZE STATUETTE, CHINA, MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY

A GILT-LACQUERED BRONZE STATUETTE, CHINA, MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY 81,5 cm high

representing Bodhisattva [..]

27

A GILT-LACQUERED BRONZE STATUETTE, CHINA, MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY

A GILT-LACQUERED BRONZE STATUETTE, CHINA, MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY 81,5 cm high

representing Bodhisattva [..]

Estimate

€ 60.000 / 80.000

Sold

1

- 27

of 27 LOTS