12

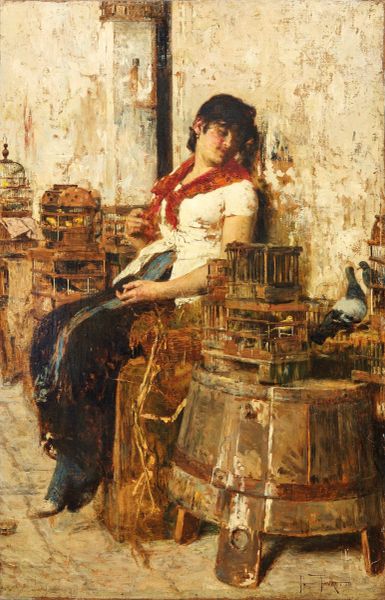

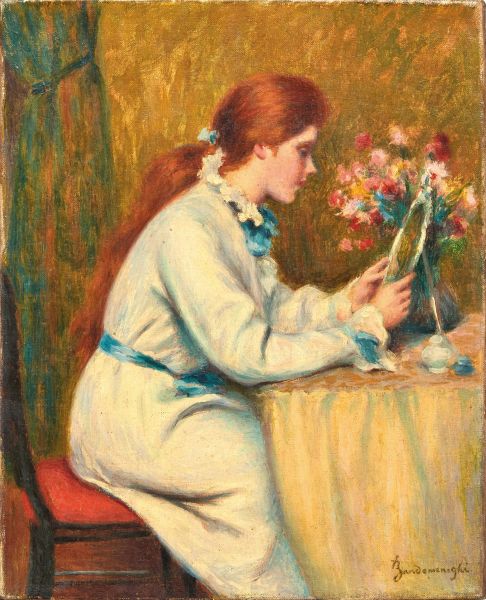

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

(Livorno, 1859 - Firenze, 1933)

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

(Livorno 1859 - Firenze 1933)

DONNA CON CANE

1885

[..]

12

Offerta Libera

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

(Livorno, 1859 - Firenze, 1933)

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

(Livorno 1859 - Firenze 1933)

DONNA CON CANE

1885

[..]

Stima

€ 80.000 / 120.000

Aggiudicazione

17

Vincent Van Gogh

(Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-oise, 1890)

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

(Zundert 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise 1890)

STILL LIFE WITH A BASKET [..]

17

Offerta Libera

Vincent Van Gogh

(Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-oise, 1890)

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

(Zundert 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise 1890)

STILL LIFE WITH A BASKET [..]

Stima

€ 280.000 / 350.000

Aggiudicazione

28

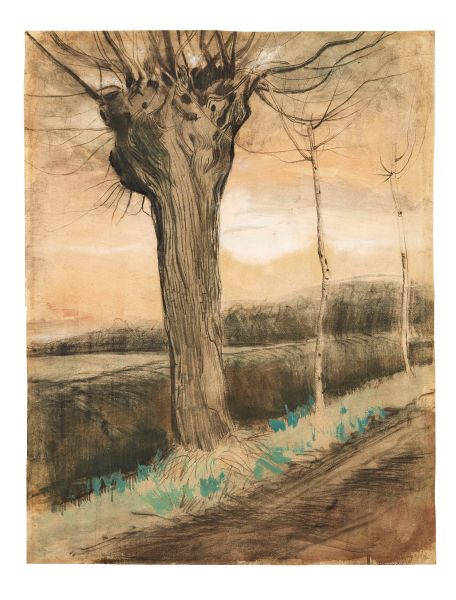

Vincent Van Gogh

(Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-oise, 1890)

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

(Zundert 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise 1890)

POLLARD WILLOW

ottobre [..]

28

Offerta Libera

Vincent Van Gogh

(Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-oise, 1890)

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

(Zundert 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise 1890)

POLLARD WILLOW

ottobre [..]

Stima

€ 200.000 / 300.000

Aggiudicazione

11

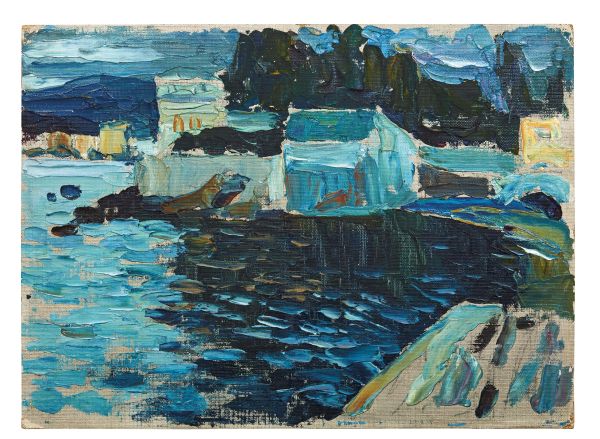

Vassily Kandinsky

(Mosca, 1866 - Neully-sur-seine, 1944)

Vassilly Kandinsky

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

SESTRI-ABENDS

1905 [..]

11

Offerta Libera

Vassily Kandinsky

(Mosca, 1866 - Neully-sur-seine, 1944)

Vassilly Kandinsky

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

SESTRI-ABENDS

1905 [..]

Stima

€ 150.000 / 250.000

Aggiudicazione

16

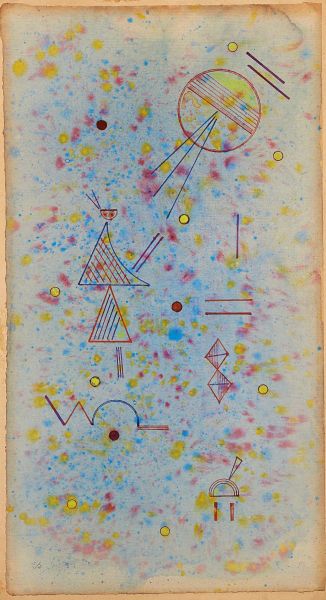

Vassily Kandinsky

(Mosca, 1866 - Neully-sur-seine, 1944)

Vassilly Kandinsky

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

DÜNN UND FLECKIG SOUPLE [..]

16

Offerta Libera

Vassily Kandinsky

(Mosca, 1866 - Neully-sur-seine, 1944)

Vassilly Kandinsky

Vassilly Kandinsky

(Mosca 1866 - Neully-sur-Seine 1944)

DÜNN UND FLECKIG SOUPLE [..]

Stima

€ 120.000 / 180.000

Aggiudicazione

24

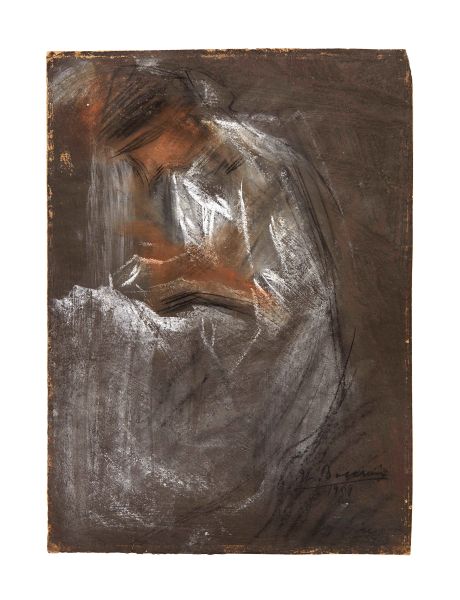

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916)

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio Calabria 1882 - Verona 1916)

DONNA CHE LEGGE

1909 [..]

24

Offerta Libera

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916)

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio Calabria 1882 - Verona 1916)

DONNA CHE LEGGE

1909 [..]

Stima

€ 30.000 / 50.000

Aggiudicazione

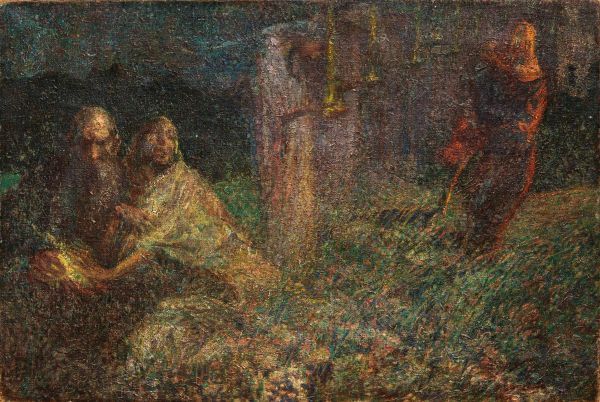

29

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916)

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio Calabria 1882 - Verona 1916)

IL FALCIATORE

oppure [..]

29

Offerta Libera

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916)

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni

(Reggio Calabria 1882 - Verona 1916)

IL FALCIATORE

oppure [..]

Stima

€ 150.000 / 250.000

Aggiudicazione

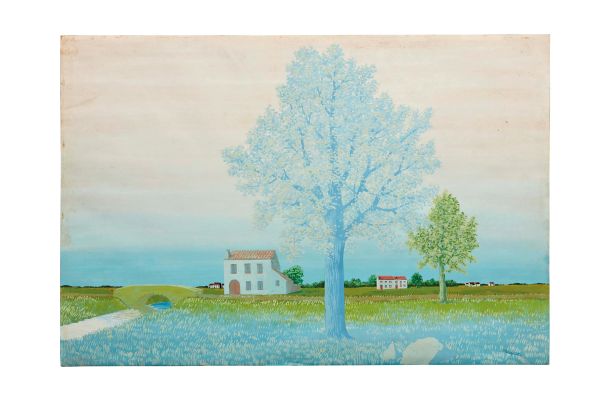

René Magritte©

(Lessines, 1898 - Bruxelles, 1967)

René Magritte

René Magritte

(Lessines 1898 - Bruxelles 1967)

LA TAPISSIERE DE PÉNÉLOPE [..]

13

Offerta Libera

René Magritte©

(Lessines, 1898 - Bruxelles, 1967)

René Magritte

René Magritte

(Lessines 1898 - Bruxelles 1967)

LA TAPISSIERE DE PÉNÉLOPE [..]

Stima

€ 90.000 / 150.000

Aggiudicazione

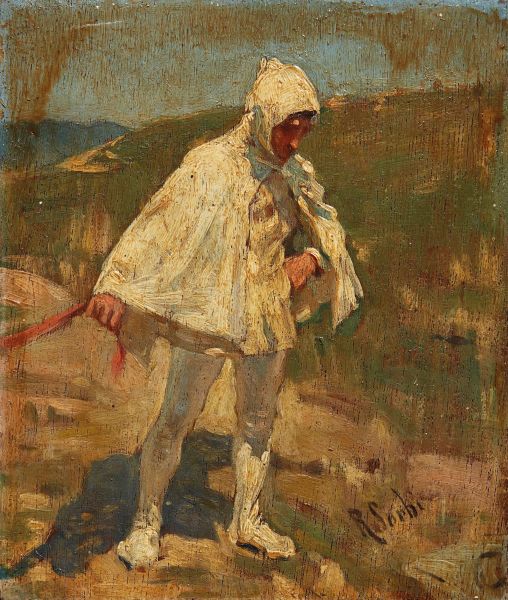

40

Raffaello Sorbi

(Firenze, 1844 - 1931)

Raffaello Sorbi

Raffaello Sorbi

(Firenze 1844 - 1931)

CIMABUE

1919 circa

firmato in basso [..]

40

Offerta Libera

Raffaello Sorbi

(Firenze, 1844 - 1931)

Raffaello Sorbi

Raffaello Sorbi

(Firenze 1844 - 1931)

CIMABUE

1919 circa

firmato in basso [..]

Stima

€ 1.500 / 2.500

Aggiudicazione

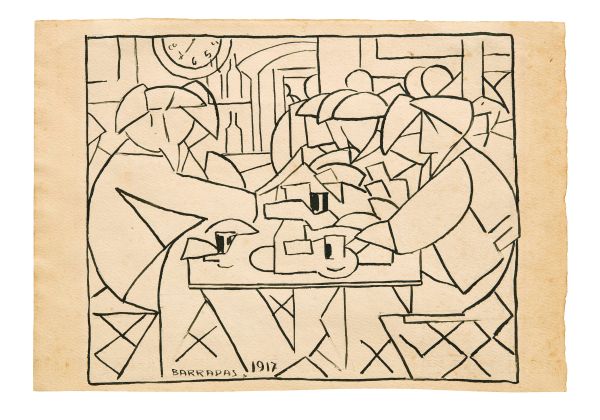

55

Rafael Barradas

(Montevideo, 1890 - 1929)

Rafael Barradas

Rafael Barradas

(Montevideo 1890 - 1929)

MENSA OPERAIA

1917

firmato e [..]

55

Offerta Libera

Rafael Barradas

(Montevideo, 1890 - 1929)

Rafael Barradas

Rafael Barradas

(Montevideo 1890 - 1929)

MENSA OPERAIA

1917

firmato e [..]

Stima

€ 1.000 / 1.500

Aggiudicazione

15

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

(Limoges, 1841 - Cagnes-sur-mer, 1919)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

(Limoges 1841 - Cagnes-sur-Mer 1919)

PAYSAGE DU MIDI

[..]

15

Offerta Libera

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

(Limoges, 1841 - Cagnes-sur-mer, 1919)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

(Limoges 1841 - Cagnes-sur-Mer 1919)

PAYSAGE DU MIDI

[..]

Stima

€ 40.000 / 60.000

Aggiudicazione

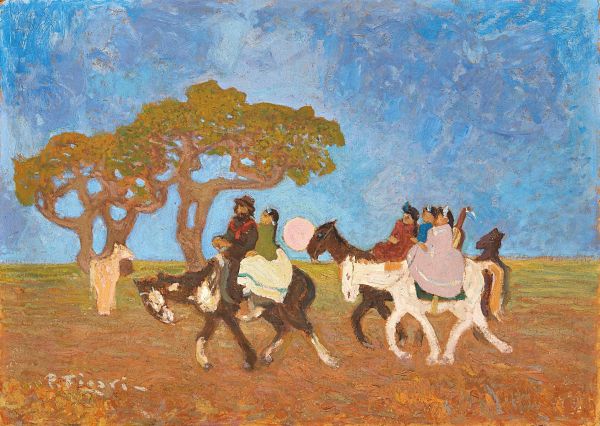

54

Pedro Figari

(Montevideo, 1861 - 1938)

Pedro Figari

Pedro Figari

(Montevideo 1861 - 1938)

A LA FIESTA

1933 circa

firmato in [..]

54

Offerta Libera

Pedro Figari

(Montevideo, 1861 - 1938)

Pedro Figari

Pedro Figari

(Montevideo 1861 - 1938)

A LA FIESTA

1933 circa

firmato in [..]

Stima

€ 4.000 / 6.000

Aggiudicazione

Pavel Mansouroff©

(Sankt-petersburg, 1896 - Nice, 1983)

Pavel Mansouroff

Pavel Mansouroff

(Sankt-Petersburg 1896 - Nice 1983)

COMPOSIZIONE ASTRATTA

[..]

51

Offerta Libera

Pavel Mansouroff©

(Sankt-petersburg, 1896 - Nice, 1983)

Pavel Mansouroff

Pavel Mansouroff

(Sankt-Petersburg 1896 - Nice 1983)

COMPOSIZIONE ASTRATTA

[..]

Stima

€ 2.000 / 3.000

Aggiudicazione

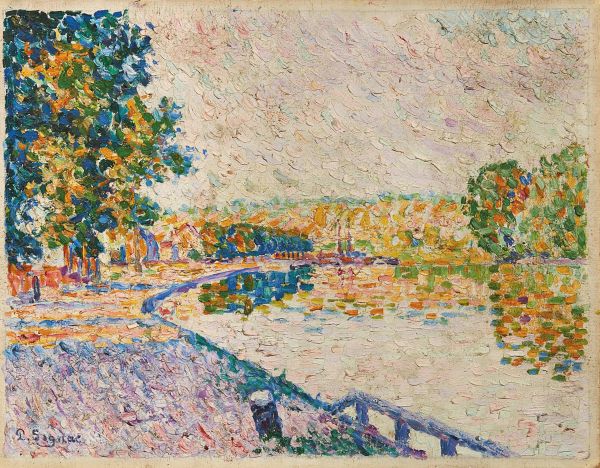

26

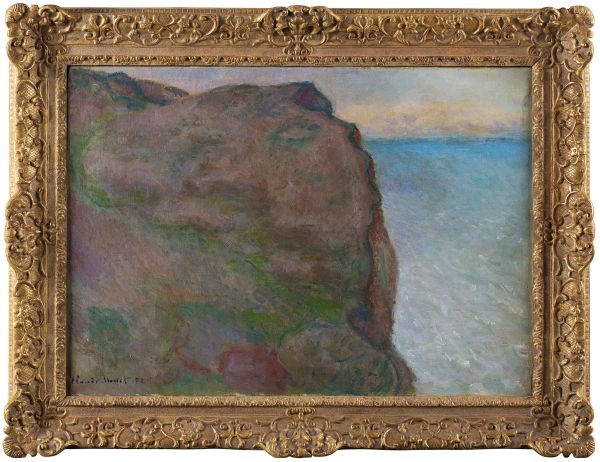

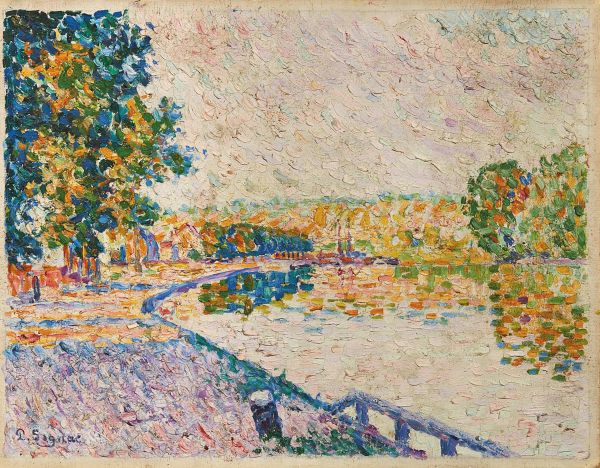

Paul Signac

(Paris, 1863 - 1935)

Paul Signac

Paul Signac

(Paris 1863 - 1935)

SAMOIS. ÉTUDE N. 11

1899

firmato [..]

26

Offerta Libera

Paul Signac

(Paris, 1863 - 1935)

Paul Signac

Paul Signac

(Paris 1863 - 1935)

SAMOIS. ÉTUDE N. 11

1899

firmato [..]

Stima

€ 120.000 / 180.000

Aggiudicazione

7

Paul Gauguin

(Paris, 1848 - Hiva oa, 1903)

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin

(Paris 1848 - Hiva Oa 1903)

JACINTHES ET POMMES SUR UN JOURNAL

[..]

7

Offerta Libera

Paul Gauguin

(Paris, 1848 - Hiva oa, 1903)

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin

(Paris 1848 - Hiva Oa 1903)

JACINTHES ET POMMES SUR UN JOURNAL

[..]

Stima

€ 150.000 / 250.000

Aggiudicazione

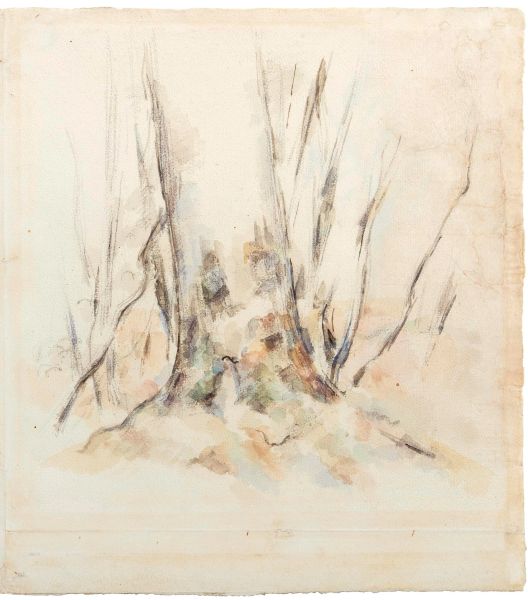

30

Paul Cézanne

(Aix-en-provence, 1839 - 1906)

Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne

(Aix-en-Provence 1839 - 1906)

LE HÊTRE

1883-1885 [..]

30

Offerta Libera

Paul Cézanne

(Aix-en-provence, 1839 - 1906)

Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne

(Aix-en-Provence 1839 - 1906)

LE HÊTRE

1883-1885 [..]

Stima

€ 80.000 / 120.000

Aggiudicazione

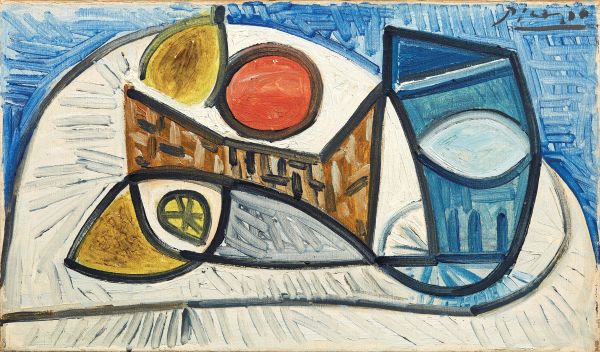

Pablo Picasso©

(Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973)

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

(Malaga 1881 - Mougins 1973)

NATURE MORTE AU CITRON, À L’ORANGE [..]

34

Offerta Libera

Pablo Picasso©

(Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973)

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

(Malaga 1881 - Mougins 1973)

NATURE MORTE AU CITRON, À L’ORANGE [..]

Stima

€ 800.000 / 1.200.000

Aggiudicazione

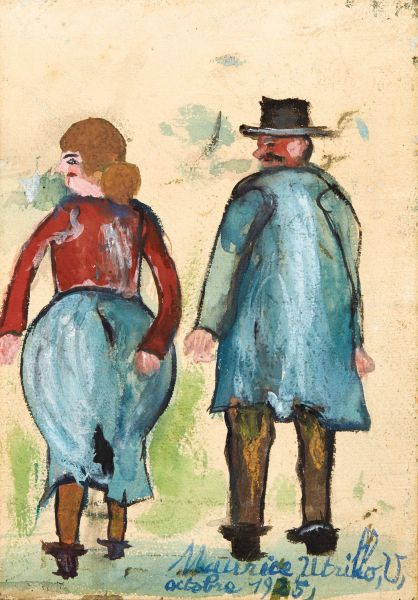

Maurice Utrillo©

(Paris, 1883 - Dax, 1955)

Maurice Utrillo

Maurice Utrillo

(Paris 1883 - Dax 1955)

LE COUPLE

1925

firmato e datato [..]

49

Offerta Libera

Maurice Utrillo©

(Paris, 1883 - Dax, 1955)

Maurice Utrillo

Maurice Utrillo

(Paris 1883 - Dax 1955)

LE COUPLE

1925

firmato e datato [..]

Stima

€ 5.000 / 7.000

Aggiudicazione

Massimo Campigli©

(Berlin, 1895 - Saint-tropez, 1971)

Massimo Campigli

Massimo Campigli

(Berlin 1895 - Saint-Tropez 1971)

BAMBINA E TARTARUGA

1952 [..]

35

Offerta Libera

Massimo Campigli©

(Berlin, 1895 - Saint-tropez, 1971)

Massimo Campigli

Massimo Campigli

(Berlin 1895 - Saint-Tropez 1971)

BAMBINA E TARTARUGA

1952 [..]

Stima

€ 2.000 / 3.000

Aggiudicazione

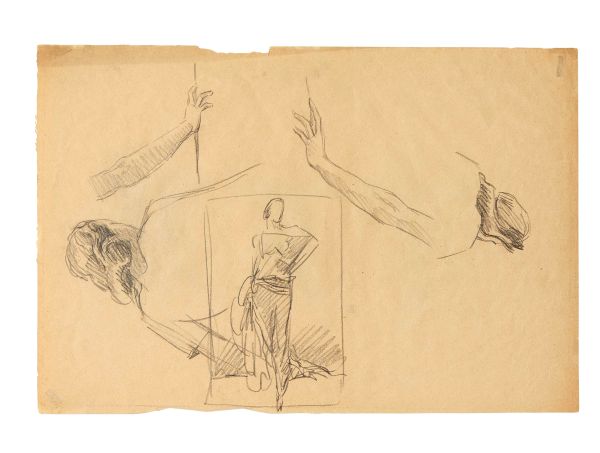

Marcello Dudovich©

(Trieste, 1878 - Milano, 1962)

Marcello Dudovich

Marcello Dudovich

(Trieste 1878 - Milano 1962)

STUDI DI FIGURE FEMMINILI ( recto [..]

52

Offerta Libera

Marcello Dudovich©

(Trieste, 1878 - Milano, 1962)

Marcello Dudovich

Marcello Dudovich

(Trieste 1878 - Milano 1962)

STUDI DI FIGURE FEMMINILI ( recto [..]

Stima

€ 800 / 1.200

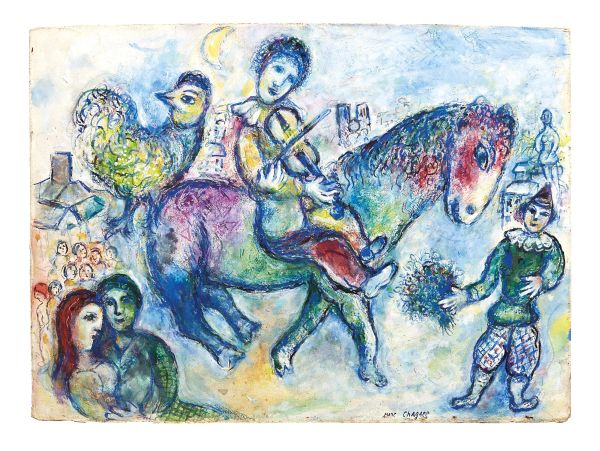

Marc Chagall©

(Vitebsk, 1887 - Saint-paul-de-vence, 1985)

Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall

(Vitebsk 1887 - Saint-Paul-de-Vence 1985)

MUSICIEN VOYAGEUR

1971 [..]

23

Offerta Libera

Marc Chagall©

(Vitebsk, 1887 - Saint-paul-de-vence, 1985)

Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall

(Vitebsk 1887 - Saint-Paul-de-Vence 1985)

MUSICIEN VOYAGEUR

1971 [..]

Stima

€ 120.000 / 180.000

Aggiudicazione

Luciano Minguzzi©

(Bologna, 1911 - Milano, 2004)

Luciano Minguzzi

Luciano Minguzzi

(Bologna 1911 - Milano 2004)

ACROBATI CONTORSIONISTI

firmato [..]

42

Offerta Libera

Luciano Minguzzi©

(Bologna, 1911 - Milano, 2004)

Luciano Minguzzi

Luciano Minguzzi

(Bologna 1911 - Milano 2004)

ACROBATI CONTORSIONISTI

firmato [..]

Stima

€ 3.000 / 5.000

Aggiudicazione

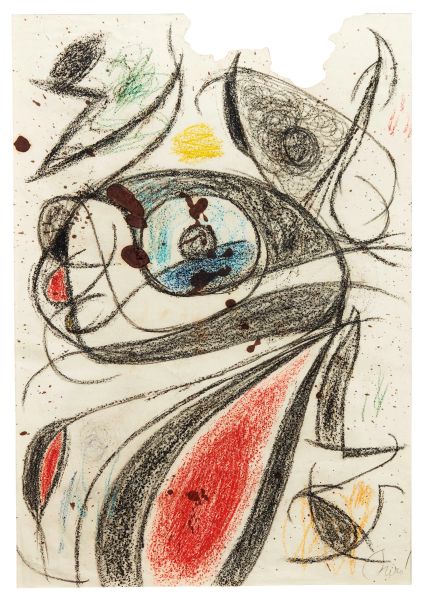

Joan Miro' I Ferrà©

(Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de mallorca, 1983)

Joan Miró i Ferrà

Joan Miró i Ferrà

(Barcelona 1893 - Palma de Mallorca 1983)

FEMME, [..]

2

Offerta Libera

Joan Miro' I Ferrà©

(Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de mallorca, 1983)

Joan Miró i Ferrà

Joan Miró i Ferrà

(Barcelona 1893 - Palma de Mallorca 1983)

FEMME, [..]

Stima

€ 30.000 / 50.000

Aggiudicazione

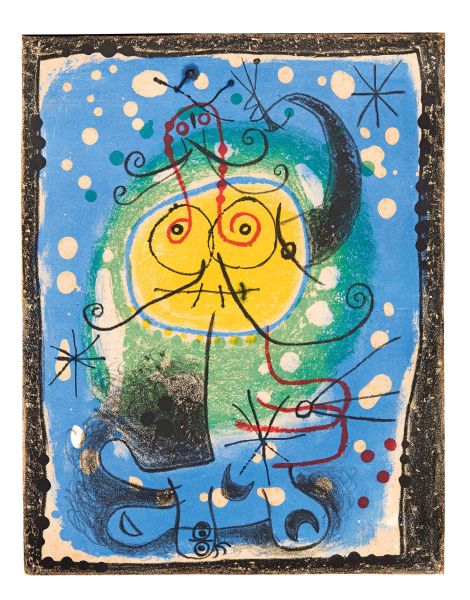

Joan Miro' I Ferrà©

(Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de mallorca, 1983)

Joan Miró i Ferrà

Joan Miró i Ferrà

(Barcelona 1893 - Palma de Mallorca 1983)

PERSONNAGE [..]

37

Offerta Libera

Joan Miro' I Ferrà©

(Barcelona, 1893 - Palma de mallorca, 1983)

Joan Miró i Ferrà

Joan Miró i Ferrà

(Barcelona 1893 - Palma de Mallorca 1983)

PERSONNAGE [..]

Stima

€ 4.000 / 6.000

Aggiudicazione

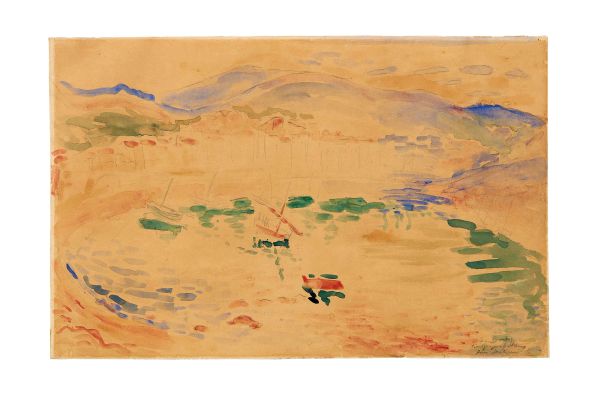

Henri Matisse©

(Le cateau-cambrésis, 1869 - Nice, 1954)

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse

(Le Cateau-Cambrésis 1869 - Nice 1954)

PORT DE COLLIOURE

[..]

20

Offerta Libera

Henri Matisse©

(Le cateau-cambrésis, 1869 - Nice, 1954)

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse

(Le Cateau-Cambrésis 1869 - Nice 1954)

PORT DE COLLIOURE

[..]

Stima

€ 30.000 / 50.000

Aggiudicazione

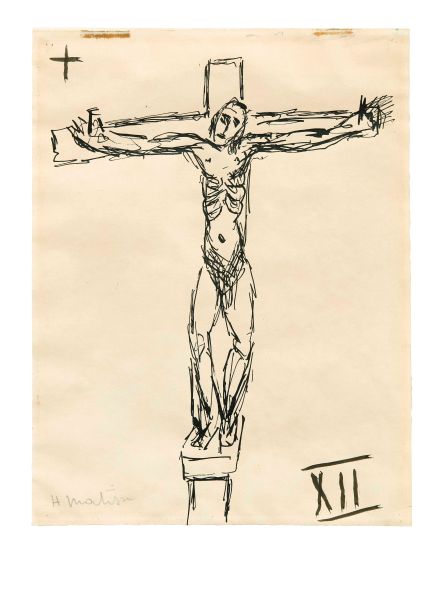

Henri Matisse©

(Le cateau-cambrésis, 1869 - Nice, 1954)

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse

(Le Cateau-Cambrésis 1869 - Nice 1954)

LE CHRIST EN CROIX, ÉTUDE [..]

33

Offerta Libera

Henri Matisse©

(Le cateau-cambrésis, 1869 - Nice, 1954)

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse

(Le Cateau-Cambrésis 1869 - Nice 1954)

LE CHRIST EN CROIX, ÉTUDE [..]

Stima

€ 10.000 / 15.000

Aggiudicazione

19

Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec

(Albi, 1864 - Saint-andré-du-bois, 1901)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

(Albi 1864 - Saint-André-du-Bois 1901)

TÊTE [..]

19

Offerta Libera

Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec

(Albi, 1864 - Saint-andré-du-bois, 1901)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

(Albi 1864 - Saint-André-du-Bois 1901)

TÊTE [..]

Stima

€ 80.000 / 120.000

Aggiudicazione

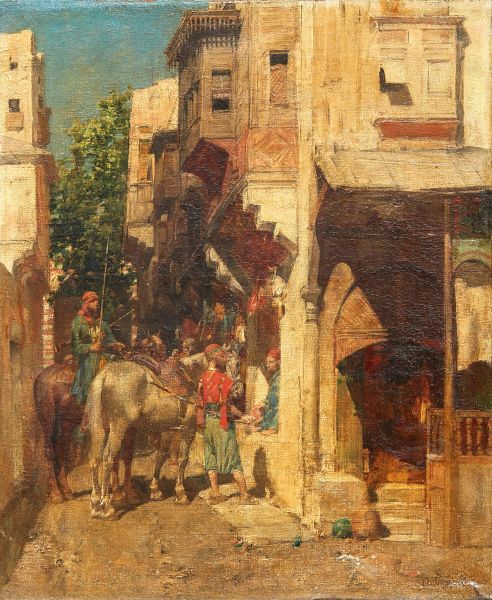

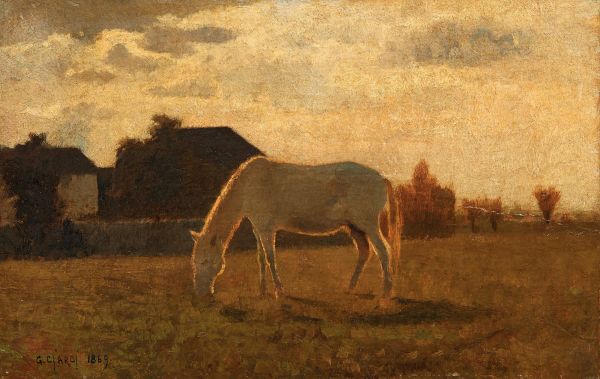

45

Guglielmo Ciardi

(Venezia, 1842 - 1917)

Guglielmo Ciardi

Guglielmo Ciardi

(Venezia 1842 - 1917)

CAVALLO BIANCO

1869

firmato e datato [..]

45

Offerta Libera

Guglielmo Ciardi

(Venezia, 1842 - 1917)

Guglielmo Ciardi

Guglielmo Ciardi

(Venezia 1842 - 1917)

CAVALLO BIANCO

1869

firmato e datato [..]

Stima

€ 5.000 / 7.000

Aggiudicazione

36

Giuseppe De Nittis

(Barletta, 1846 - Saint-germain-en-laye, 1884)

Giuseppe De Nittis

Giuseppe De Nittis

(Barletta 1846 - Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1884)

UOMO CON CAPPELLO [..]

36

Offerta Libera

Giuseppe De Nittis

(Barletta, 1846 - Saint-germain-en-laye, 1884)

Giuseppe De Nittis

Giuseppe De Nittis

(Barletta 1846 - Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1884)

UOMO CON CAPPELLO [..]

Stima

€ 12.000 / 18.000